How Concerned White Citizens Marched in Selma Before Bloody Sunday

Warning: This is a speech I gave recently in Selma at the “Highway 80 History Symposium” It’s longer than I normally post, but I believe it is timely.The content is based on a portion of research from my nonfiction book Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days.

A small thing made all of human civilization possible. It is often overlooked and undervalued, but it is so much a part of our lives that we don’t pay much attention to it. We did it even before we developed language, and we still do it. It is a deep part of who we are as a species, and it is so powerful that it can change everything.

What is it? What made human civilization possible?

We tell stories. Stories did and do more than convey information; they instilled the values that kept communities together and built civilization.

In Israel, when the Holocaust Memorial organization finds stories about non-Jewish people risking their lives to save Jews, they honor the person by naming them “Righteous Among the Nations.” The fact that those people were exceptions among a majority who did nothing to help or even were complicit in the atrocities only underscores the risks they took and their courage. It is important to honor and remember them and their deeds.

History bears witness to terrible injustices in the name of one group claiming superiority over another, a pattern repeated throughout our species’ story. It is a sad fact that America’s example of racial discrimination reinforced Adolf Hitler’s ideas about the superiority of what he called the “Master Race.” But it is also a fact that stories about the peaceful, brave resistance to racism and Jim Crow here provided courage and inspiration to the world.

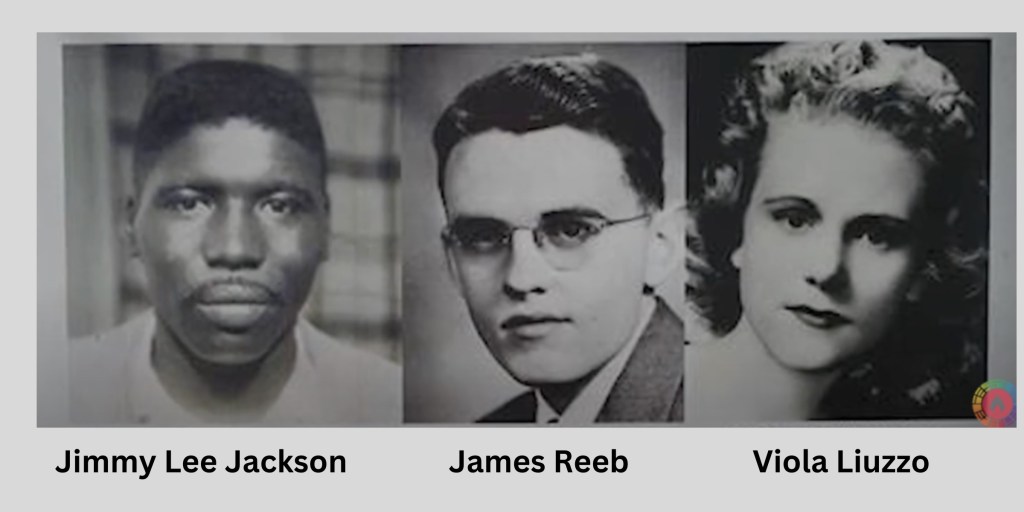

We are familiar with the stories of the struggles for voting rights in the South, particularly the Black Belt. We know that Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young black man, was shot and killed when he attempted to defend his mother against a beating by a law enforcement officer. We know his death inspired the Selma marches. We know about the cruelty of Bloody Sunday, the batons and tear gas, and the political maneuvering that finally allowed the march to Montgomery.

We know that Reverend James Reeb, a White Unitarian minister from Boston, and Viola Gregg Liuzzo, a White woman from Detroit, were also murdered for their participation in the marches and that White people from across the country came to join Martin Luther King and John Lewis to make that symbolic trek to the state capital.

But a story got lost in the shadows cast by those portentous days, a story we need to hear and remember.

It began in Birmingham, Alabama, where a small group of Black and White people, the Council on Human Relations, had been meeting since the 1950s, despite Jim Crow laws that forbid them to do so. They met in the Black First Congregational Church, which welcomed them. The women made a point to socialize in each other’s homes and to get to know one another as friends. By 1964, they would name their group “Friends and Action” and take on projects in the community. They offered classes for Black students, started an integrated Head Start playground, sent mixed groups of youths to experiences out of state, obtained lab equipment for Miles College, and invited speakers to the Unitarian Church.

Two of the White women, disturbed by the events in the Black Belt, made a trip to Selma to “see for themselves” how the Dallas County Sheriff’ Jim Clark’s department was suppressing Black voter registration and terrifying the Black community. They returned to report what they had seen.

The group requested one of the activists come to talk to them. Hosea Williams came to Birmingham and told them about the cruelties imposed on Blacks who registered to vote or attempted to and about Jackson’s murder.

Distressed, one White woman asked, “What can we do to help?”

Williams replied, “I’ll tell you one thing you can do to help. You can take some warm, white bodies down there and show you care.”

Divided about what to do and fearful of taking such risks, the group argued. But one woman stood up and said she was “tired of having Black people do all the work. I don’t care if anyone else goes to Selma. I’m going if I have to go alone.” One of the women who had gone to Selma to see for herself, joined her. Their determination moved others.

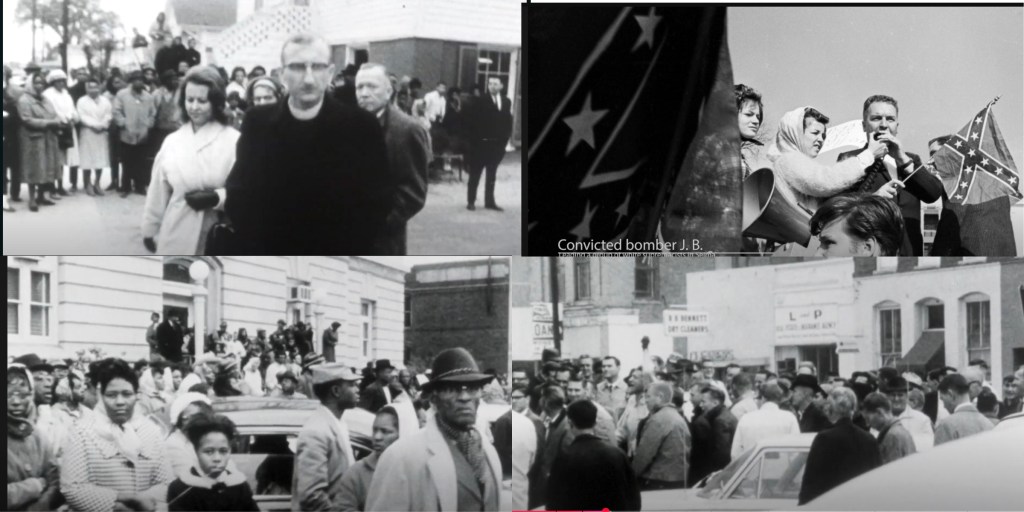

Led by the Reverend Joseph Ellwanger of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, the group made phone calls and sent delegations to other Whites throughout Alabama to rally in Selma with a march to the courthouse. Brief newspaper coverage brought in warm letters and contributions from across the country.

With only ten days’ notice, seventy-two White people—forty-six from Birmingham—answered the call. They were Christians and Jews from across the state. When the group arrived in Selma, they were welcomed at the Reformed Presbyterian Church by the SCLC’s James Bevel and Father Maurice Ouellet, who, like Ellwanger, served a Black congregation. One recalled that “quite a few Blacks were there. They were so happy and so astonished. They were just not used to having Whites come on their side.”

Another White protestor, speaking unknowingly to a New York Times reporter, said, “‘We have remained silent for a long time, trying to give moral support to Negroes. I felt it was time to show that a group of demonstrators can have a face other than that of the Negro.”

From Broad Street, the group marched two by two with signs reading, “Silence Is No Longer Golden” and “Decent Alabamians Detest Police Brutality.”

At Alabama Street, Rev. Ellwanger, who led the group, recalled, “…on our right were about a hundred white men . . . with baseball bats or pipes and using foul language to let us know what they thought of us. To our left, on the far side of the intersection, in the street, and on the grassy area around the federal building were about four hundred blacks shouting words of encouragement.”

Members of SNCC, the Students Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who had been working for voting rights in Selma, advised the White marchers, who did not have a permit, to follow the law by walking in pairs a few feet apart, and to ignore the taunts, shouting, and spitting. Dressed in their Sunday best, the marchers walked on. They were prepared to be arrested, but that was not their purpose.

One of the women recalled, “You could feel the danger in the air, the hatred. We had to keep our faces straight ahead. We were just there to let people know that there were white people in Alabama who believed blacks should have equal rights. ”

Amelia Boynton, a longtime activist in the Dallas County Voters, was among the Blacks watching. “I can never do justice,” she later said, “to the great feeling of amazement and encouragement I felt when, perhaps for the first time in American history, white citizens of a Southern state banded together to come to Selma and show their indignation about the injustices against African Americans. . . . They had everything to lose, while we . . . had nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

Past the jeering mob, Ellwanger led his group to the courthouse steps, where he read their proclamation protesting the treatment of arrested Negroes in keeping them from voting and gathering in lawful assembly.

When he finished, seventy-two voices lifted in “America the Beautiful.”

The hostile mob tried to drown them out with “Dixie.”

But from across the street, the hundreds of Black witnesses joined in with their strong voices to finish “America the Beautiful” and sing together, “We Shall Overcome.”

After Reverend Ellwanger read their proclamation, they were able to get back to their vehicles—by dent of luck and the fact that Sheriff Jim Clark was not in town—and shake the pursuit of two carloads of Klansmen.

But there were consequences. Those involved in the marches were subjected to harassing and threatening calls, and at least one man encountered a cross burning in his yard and a mob’s demand to leave town. Money had to be raised for guards around Rev. Ellwanger’s church and residence. One woman’s car was pushed over an embankment, and she lost her job at a suburban newspaper. A businessman discovered all the windows at his wholesale furniture business broken. His customers received anonymous warnings that if they bought furniture from him, they would find broken windows at their own companies. Overnight, he lost his business. If the Klansmen chasing their cars had caught up with them, the cost of their stand might have been much steeper.

The lesson from this remembrance of the “Righteous Among Alabamians” is that standing up matters and stories matter. Both show us what is possible, even in times of darkness, feeding the embers of hope into the fires of courage. History bears witness to terrible injustices in the name of some claiming superiority to others. But we also have the capacity to see ourselves in each other and work toward a world that reflects that. Hearing and understanding history’s stories helps us perceive and understand our choices. Our future depends on which paths we take.

I write about what moves me, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination.

Feel free to explore my website, but if you arrived by way of my blog on Substack, here’s the way back.

If you arrived by way of the “The Stiletto Gang,” a fun daily blog by mystery authors, here is your ticket there.

Discover more from T. K. THORNE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

So timely and so needed right now. Thank you, T.K.!

Thank you for this account of the white march. It has gotten too little attention, probably, in part at least, because of Bloody Sunday the next day. As a participant in the march and Friendship and Action, I was especially glad to see it.

Marcia E. Herman-Giddens

Thank you, Lois.

Marcia, I am sure I did not do your bravely justice! Thank YOU for being willing to take such a risk to speak for all of us. Let me know if I got anything wrong or if there is something you think needs to be included. I gave this as a presentation in Selma and might have an opportunity to do so in D.C. next month. (I don’t think I knew you when I was writing it, or I would have jumped at the chance to talk with you.)

I thank you for publicizing our march. Your account looks accurate as far as I know. We had a bit of training in non-violence in the basement of the church. We didn’t have a parade permit so had to walk in a certain pattern. I got spit on. I wrote more about it in my book, “Unloose My Heart.” As far as I know, my chapter about the march was the first time details about it had been published in a book.

I read your book and loved it. I had forgotten that detail about you being spit on. I will include that. Do you know if others experienced that as well?

As far as I know, I am the only one that happened to but a few others were pushed or jostled. I was on one end of a 4 person line, hence, the woman that spit on me was able to hit me. I describe the feeling in my book. Even with my poor memory I never forgot that.

I imagine not. 😦

Thanks for reminding us of this important lesson. It certainly is timely!

Thank Sue! Tough times, indeed!